Fuel prices, extreme weather & heat pumps driving changes

By John Ackerly & Caroline Solomon

With rising gas, oil and electricity prices, wood and pellet stove manufacturers are struggling to keep up with a demand not seen in more than a decade. In Europe, demand for stoves is even larger, with lines forming outside hearth stores in hopes of getting one installed before the next heating season.

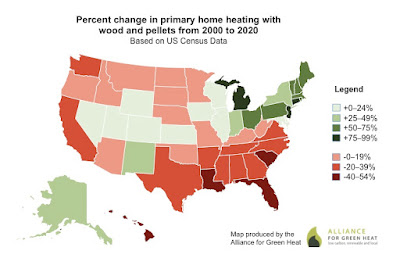

This recent surge comes on the heels of major demographic shifts already underway in wood and pellet heating in America. Households in southern states are retiring old stoves and not buying as many new ones, while in many northern states, demand has been surging. And while wood and pellet stoves are far more dominant in rural areas, there has been significant growth in some urban areas in recent decades.

From 2000 to 2020, the number of U.S. homes using wood and pellets as a primary heating fuel grew very slightly, from 1.68% in 2000 to 1.70% in 2020, based on U.S. Census data. In real numbers, that means 2,075,845 households are using wood or pellets as a primary fuel. An additional 8 to 9 million homes use wood or pellets as a secondary heat source, making it the most popular secondary heating fuel after electricity. (The US Census gathered this data in 2000 and 2020 by asking the following question: “Which FUEL is used MOST for heating this house, apartment, or mobile home?”)

However, this national data obscures some important local and regional trends. In some urban areas, wood heating is growing rapidly, while in some states it is falling rapidly. This is one of the first analyses based on US Census data to identify these trends in wood heat, which have been playing out over the last 20 years.

Overall, the only sources of heating that are rising between 2000 and 2020 are electricity, solar and wood, although wood only had a tiny rise. Fuel oil, propane, coal and gas all fell.

|

| Based on US Census Data. Compiled by the Alliance for Green Heat. |

Urban vs. rural wood heat trends

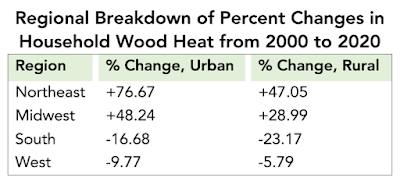

On average, urban areas in the US saw an increase of 7.05% in wood heat, while rural areas saw an increase of 5.58%. But in 3 states, the number of homes using wood or pellets in urban areas more than doubled, and nearly doubled in 2 other states.

|

| Based on US Census Data. Compiled by the Alliance for Green Heat. |

Michigan and Pennsylvania are both in the top 5 states for wood heating growth in urban and rural areas. Interestingly, the fastest growth in rural areas is not in the states where wood heating is most common. It’s important to note that the rapid increase in wood heat in some states does not always correlate with stove sales. One possible explanation is that many homes that used their stoves as a secondary heater in 2000 are using it as a primary heater in 2020.

For the Northeast and Midwest, the urban change is much higher than the rural change; and in the South, urban wood heat usage is decreasing at a slower rate than rural wood heat usage. The West is the only region in which urban wood heat usage is falling more quickly than rural usage.

But wood and pellet heating remains mainly a rural phenomenon. About four times the number of homes heat primarily with wood or pellets in rural areas than they do in urban areas. As a percentage, in 2020 less than half a percent of urban homes heat with wood but nearly 7% of rural ones do.

More than 80% of Americans live in areas classified as “urban” by the US Census, which includes thousands of towns and suburban areas around cities. In 2010, Census data found 57% of households who primarily heat with wood live in rural areas, 40% in suburban areas and only 3% in urban areas.

The growth of wood heat in urban areas may reflect a much faster growth of pellet stoves, compared to wood stoves. In some states, hearth retailers sell more pellet stoves than wood stoves. Nationally, experts often say that about a one quarter to one third of all stove sales are pellet stoves, but there is no reliable data indicating exact percentages or where they are installed. Some urban areas, in addition to areas that experience frequent weather inversions, are beginning to ban the new installation of wood fireplaces and wood stoves. This is an effective way to ensure wood smoke does not get much worse where wood stoves are already common. For the smoke issues that do remain in more urban areas, wood smoke is primarily driven by outdoor fire pits, chimmneys and fireplaces.

In one of the only academic studies of U.S. wood heating trends published in 2012, the authors identified changes in wages and other energy prices as key drivers of demographic shifts in wood heat usage. That study, Analysis of U.S. residential wood energy consumption: 1967–2009, is an excellent overview of many factors impacting wood heat, and was done at the end of a 4-decade period of gradual decline in wood heat. This was before wood heat began trending up in 2000, ending its decades-long decline.

Little research has been done in recent years on wood and pellet heat usage in urban and rural areas. One of the very few comprehensive analyses of U.S. wood heat usage, a report from 2012, called its lack of a breakdown of urban vs. rural wood heat as a “shortcoming” that was due to a “lack of time series data corresponding to urban/rural areas.”

State and regional wood and pellet heat trends

The states with the highest percentage of homes using wood or pellets as a primary heating fuel have remained relatively steady over the years. New Mexico was ranked sixth in 2010, quickly rose to third place in 2019, and then dropped back to fourth in 2020. One potential reason there could be more rapid changes in primary heating with wood and pellets is that a stove can be a primary heater one year and a secondary heater the next, which is usually not the case with central heating systems using oil, gas or electricity for fuel.

|

| Based on US Census data. Compiled by the Alliance for Green Heat. |

Many states experienced dramatic increases in wood heat usage from 2000 to 2020, while others saw declines in wood heat. The majority of the states which saw an increase in wood heat were not in New England and the Pacific Northwest where it is most popular, but in second tier states a bit further south. States where wood heat dropped the most are the warmest, southernmost states in the country.

|

| Based on US Census Data. Compiled by the Alliance for Green Heat. |

Aggregating by region, the general trend seen with states located in northern vs. southern regions holds. The two regions that saw increases in wood heat were the Northeast (+51.05%) and the Midwest (+27.73%), while the South and the West both saw overall decreases (-28.31% and -9.94%, respectively).

|

| Based on US Census Data. Compiled by the Alliance for Green Heat. |

Selected state graphs

The residential heating mix in each state tells a different story over the years and presents different challenges to lowering the greenhouse gas intensity of heating fuel.

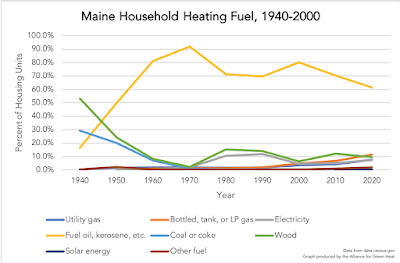

Wood and pellet heating has typically been the second most common primary heating fuel in Maine after oil. Wood did not prove to be any more popular in Maine in 1970 than it did in the rest of the country, but when heating oil costs rose, wood heating bounced back in a much dramatic way.

Wood heating in Washington state closely parallels Maine, starting at over 50%, diving to under 2% in 1970 and then rebounding in 1990. Electricity, however, has been extremely popular in Washington, probably due to milder winters, and local, cheaper hydroelectricity.

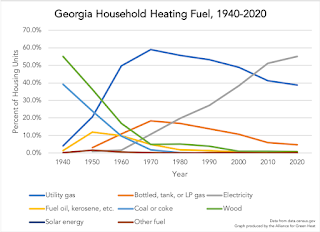

One of the largest, unknown stories about wood heat is that it was far more popular in the south in the 1950s, 60s and 70s than the rest of the country, including New England. This was largely because many rural Black communities were not included in gas or electricity infrastructure projects that enabled wealthier communities to get off wood and coal. Many households that rely on wood heat to this day do so not out of choice but out of necessity, and represent a significant, though little-noticed, energy justice issue.

Policy considerations

The rapid rise of wood heat presents a number of policy considerations that are frequently overlooked. Wood and pellet heating is often seen more of a public health nuisance in some circles, an energy lifeline in others, and a solution to shed fossil fuels in others. All of these narratives are valid and must be balanced at the local, state and federal level.

Lack of understanding of the issues is a major barrier, as many policymakers and organizations often confound the issue of burning industrial pellets to make electricity with the sustainable use of premium pellets for local heat. And many still assume wood heat primarily involves cutting live trees, instead of sourcing wood that is already down or dead and has no other use. There is little awareness that pellet heat is consistently far cleaner than cord wood heat. Finally, there is still a lack of awareness that wood smoke, which may smell good to many people, is a serious health issue.

If utilizing the cleanest and most modern wood and pellet heating to reduce fossil fuel use was the goal, federal and state governments could focus tax incentives and rebates on pellet stoves and boilers, as some states already do. Already in Vermont and other areas, the high rate of wood and pellet heat reduces stress on the grid during winter peak load periods, which are likely to get worse as more of our energy needs are electrified. If the federal government wanted to support rural low-income families to utilize free local wood, it could drastically increase its R&D funding to jumpstart the production of automated wood stoves that use computer chips to regulate air supply and prevent smoldering.

We can expect some cities and states to restrict new installations of wood heaters in densely inhabited areas and others to expand modern, automated heat at the commercial and residential level. Such outcomes are not inconsistent but require more educated debate among policymakers and the public. Already some of these policies are helping to shape the rise and fall of wood and pellet heat across America, but are likely a small influence compared to market forces.

Conclusion

While wood and pellet heating has changed little in the last 20 years at the national level, regional and state changes have been significant. At a national level, studies show that reductions in household size, growth in heated floor area per house, and increased access to space cooling are the main drivers of increases in energy and GHG emissions after population growth. Improved generation efficiency and decarbonization of electricity supply are bringing about GHG emission reductions. Wood and pellet heat may be on the rise again, meaning it could factor more into national discussions of energy security and decarbonization.

This paper looks at the size of primary wood and pellet heating at the national and state level, but the role of secondary wood and pellet heating is equally, if not more, important in terms of sheer BTU output and reductions in fossil fuels. Similar challenges of understanding, guiding and managing the pros and cons of wood heat are emerging across the northern and southern hemisphere and particularly in Europe, where the energy implications of Russian’s invasion of Ukraine are most acute.

The next 20 years will likely see an even more rapid shift in residential heating fuel, as climate change becomes a more urgent issue. Electrification is emerging as the dominant, most obvious solution to home heating but wood and pellet heating may emerge as larger factor in the Northeast region and in various other states.

Further Reading